In sheet metal design, progressive ribs (also known as strengthening ribs) are raised or embossed features formed into a panel to significantly increase its rigidity and resistance to bending without adding excessive weight. By adding depth and contour to what would otherwise be a flat sheet, ribs greatly improve the panel’s moment of inertia – meaning it can support greater loads without sagging or “oil canning” (flexing) under stress. In essence, a rib acts like an internal support beam or tiny corrugation within the sheet, effectively increasing the material’s stiffness as if it were thicker. This strength boost comes with minimal weight penalty because the material is redistributed in shape rather than added in mass. Progressive ribs are a common technique to reinforce thin-gauge components in weight-sensitive applications (like automotive or aerospace), achieving stronger parts that remain lightweight.

Structural Benefits of Strengthening Ribs

Flat sheet metal panels are inherently prone to bending under load. Adding stiffening ribs introduces geometric ribbing that dramatically increases a panel’s stiffness by increasing its cross-sectional area and moment of inertia. Even a shallow rib feature can substantially raise the load-bearing capacity of a sheet by providing extra depth and shape, allowing the panel to support heavier loads over wider spans without deforming. Importantly, this is accomplished without a significant weight increase – the sheet’s material and thickness remain essentially the same, just formed into a stronger profile. In other words, a thin-gauge part with well-placed ribs can often perform like a much thicker, heavier part, which is a key advantage in optimizing material usage.

Beyond pure load capacity, ribs offer several additional benefits:

- Stress Distribution: Ribs help spread forces more evenly across the sheet, reducing concentrated stress points. This improves durability and fatigue life since the metal is less likely to buckle or crack at a single spot under repeated loads.

- Vibration Reduction: Increasing a panel’s stiffness with ribs raises its natural frequency and reduces flex, which in turn diminishes vibration and noise. For example, appliance panels or vehicle floorboards with stiffening beads tend to rattle and “oil can” less during operation. (Designed-in stiffening ribs are even used as a noise-reduction measure in some soundproofing solutions in automotive designs.)

- Aesthetic or Functional Features: Ribs can double as design elements or functional add-ons. They may serve as decorative lines on a surface, or create clearance channels and alignment features. For instance, an embossed rib can provide a wiring channel or prevent two components from rubbing together. Fabricators often use ribs (or similar embossed beads) to add such clearances for hardware and to enhance product appearance – all while also benefiting the part’s strength.

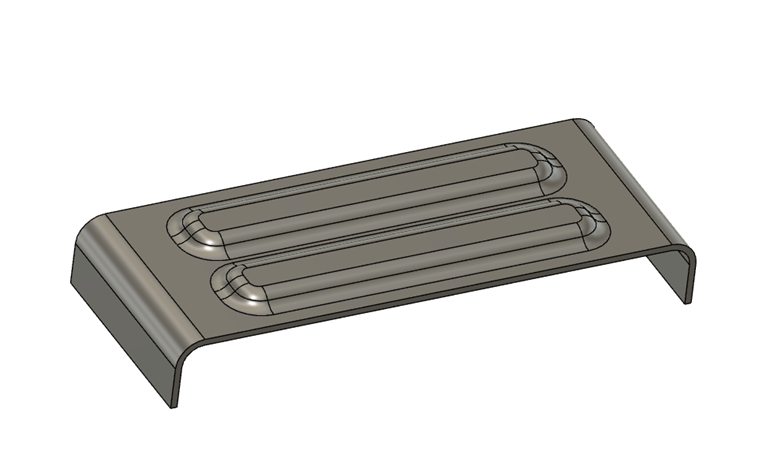

Example of a sheet metal bracket with two long embossed ribs to increase rigidity. These ribs act as built-in reinforcements, significantly stiffening the flat section without adding separate parts or weight. In this example, ribs formed into the bracket’s flat web prevent flexing under load, avoiding the need for a thicker plate or additional welded stiffeners. This design approach keeps the part lightweight and cost-effective while improving its structural performance.

Manufacturing Techniques for Ribs

There are several manufacturing approaches to create ribs in sheet metal parts, each suited to different production volumes and rib geometries. Common techniques include stamping, CNC punch/embossing, bending/forming, and roll forming. Below we outline how each method works and where it’s applied:

Stamping (Press Dies)

- High-Volume Production: Stamping is ideal for mass production. In a stamping press (or as one station of a progressive die), a dedicated tool punches a rib shape into the sheet in one stroke.

- Deep, Well-Defined Ribs: This method can produce crisp, deep ribs in a single operation. For example, automotive body panels and floor pans often have stiffening beads formed by stamping; a truck floor pan might have ribs on the order of ~3/8″ deep stamped in for strength.

- Fast Cycle, High Tooling Cost: Stamping offers excellent consistency and very fast cycle times per part, but requires expensive custom dies. It’s most cost-effective when amortized over large production runs.

CNC Punching and Embossing (Trumpf Technology)

- Flexible, Mid-Volume Production: CNC punching allows adding ribs without dedicated hard tooling. Using a punch press, you can form ribs with a beaded emboss tool programmed into the machine. This is great for moderate volumes or prototyping where building a big die isn’t justified.

- Discrete Hits vs. Continuous Ribs: A simple approach is to punch a series of short embossed hits that overlap to create a long rib. However, making a long rib by many successive punches can be time-consuming and may leave slight witness marks where each hit occurred.

- Trumpf Roller Beading: Advanced CNC machines (like Atlas’s Trumpf machines) use roller tooling to form continuous ribs in one pass. In this process, the punch press holds the sheet and tool in contact and “rolls” the rib shape dynamically across the sheet, rather than multiple discrete hits. This produces a smooth, uniform bead with no step marks, even for curved or very long ribs. The speed is also a huge benefit – what might take tens or hundreds of punch hits (and several minutes) can instead be done in just a few seconds with a rolling tool. The result is high-quality ribs formed right on the punch press, with no secondary operation needed. Atlas leverages Trumpf roller beading technology to efficiently add stiffening ribs with high precision and consistency. (As a bonus, Trumpf’s CNC control can even vary the rib depth on the fly to fine-tune quality in different areas of the part.)

Bending/Forming

- Formed Flanges and Offsets: In some cases, a “rib” is created by bending the sheet itself (for instance, forming a flange, jog, or rib feature on a brake press). Small bends or flanges can act as ribs along edges or within brackets.

- Edge Stiffening: A common use is bending the edges of a panel (like a shallow Z-shaped offset or flange) to stiffen what would be a floppy edge. This is often done with press brake tooling or custom dies to add ribs or gussets in low-volume parts.

- Low-Volume or Thick Material: Forming ribs by bending is practical for low-quantity parts or thicker sheets where embossing might be difficult. It’s a simple method but limited in that it usually creates relatively short or straight rib features (as opposed to complex curved beads).

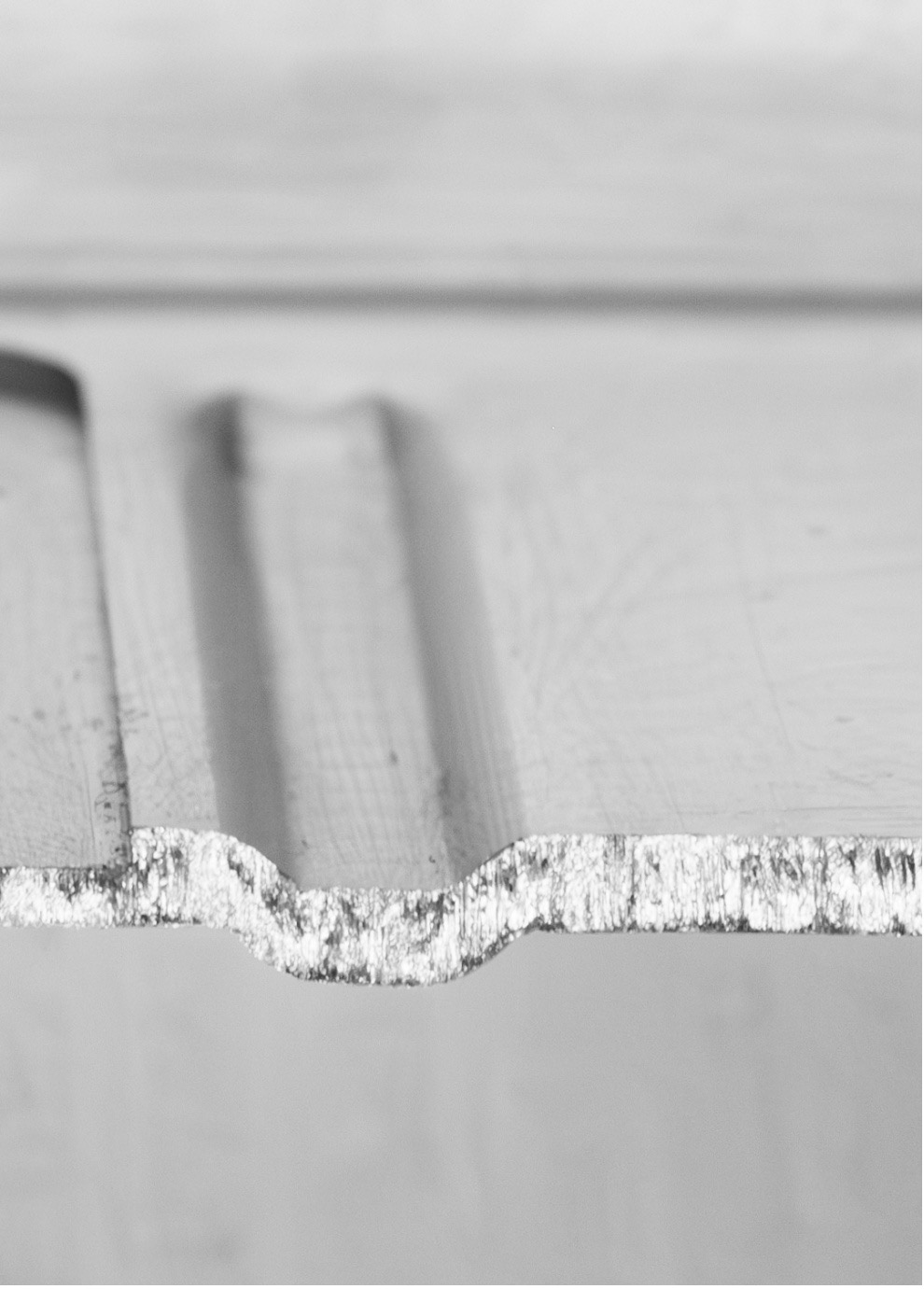

Roll Forming

- Continuous Ribs in Large Panels: Roll forming is a process where sheet metal is fed through a series of roller dies to progressively form a continuous profile along its length. This is commonly used to produce corrugated panels or decking with repeating ribs.

- Efficient for Long Runs: If you need very long panels with ribs (for example, HVAC ducts, roofing sheets, or siding panels), roll forming is extremely efficient. It can create a pattern of ribs across an entire panel width in a continuous operation.

- Profile Limitations: Roll forming excels at making repeating rib patterns (like the waves in corrugated metal roofing). It’s less flexible for custom or localized ribs – the rib pattern is fixed by the roller die setup. Also, tooling changes are needed to alter rib designs. But for high-volume production of standardized profiles, it’s unbeatable in speed. (Many air-conditioning and heating ducts, for instance, get their characteristic beaded reinforcements through a roll-forming process.)

Design Considerations for Effective Ribs

Designing ribs into sheet metal requires balancing strength goals with manufacturability. Key factors to consider include rib shape, dimensions, placement, orientation, and material constraints:

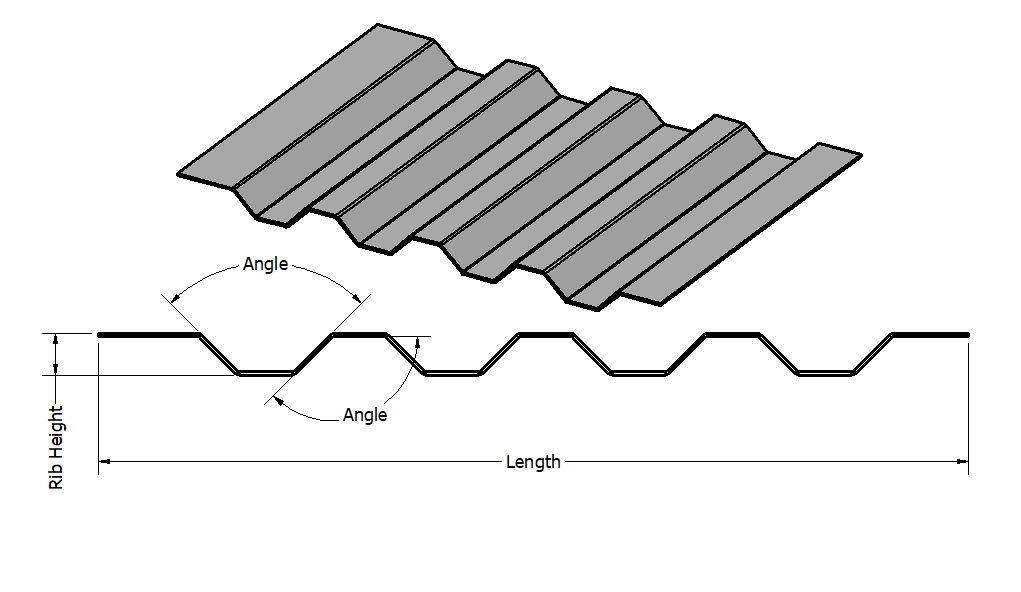

Rib Shape

- Rounded (arched) ribs: These ribs have a curved, smooth profile (like a shallow dome or half-cylinder shape). Rounded ribs are generally easier to form because they don’t have sharp corners – the material flows gradually, reducing strain. They also distribute stress more evenly, minimizing stress concentrations. However, they may not be as stiff as a taller rib with flat walls, and the rounded top means less contact area if something rests against it.

- Flat-topped (trapezoidal) ribs: These ribs have a flat plateau with angled sides (resembling a trapezoid in cross-section). Such ribs can achieve greater stiffness and section modulus for a given height, and the flat top provides a broad contact surface (useful if the rib needs to interface with other parts). The trade-off is that the sharper bends at the corners are harder to form – they require enough radius to avoid cracking, and more force to achieve. The choice of rib shape often comes down to clearance and stiffness needs versus ease of manufacturing. If you have the flexibility, a gentler curved rib is more forgiving to make, whereas if you need maximum rigidity or a flat mating surface, a trapezoidal rib might be preferable.

Cross-sectional profile of a corrugated sheet with trapezoidal ribs. Trapezoidal (flat-top) rib shapes provide high rigidity and a broad surface, though they require sharp bends. In designs where formability is a concern, using a more rounded rib profile can reduce the risk of cracks, while trapezoidal ribs are chosen when maximum stiffness or a flat contact area is needed.

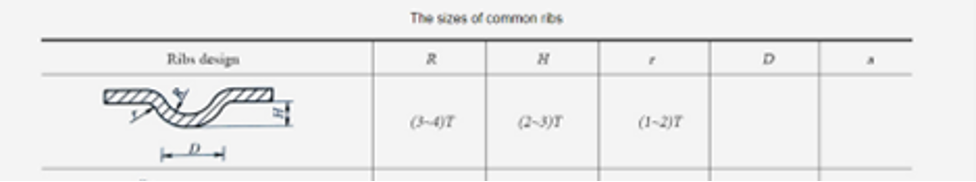

Rib Dimensions (Height & Radii)

- Optimal height-to-thickness ratio: There is a practical limit to how tall a rib can be made in a given sheet thickness. As a rule of thumb, rib height is often kept to around 3–4× the sheet thickness. Very tall ribs are prone to material thinning or splitting during forming. For example, one guideline is to ensure the inside bend radius of a rib is not more than about 3× the material thickness. Keeping the rib’s corners generously radiused (rather than sharp) helps the material stretch into the shape without tearing.

- Avoiding cracks and distortion: Sharp corners or too-high ribs can crack the sheet or create warping. Design ribs with smooth transitions – use fillets at the base of the rib and avoid extremely narrow rib widths. If a deeper stiffener is needed than what the material can handle in one go, consider multiple smaller ribs or a different reinforcement approach. The rib depth should also account for any required clearances (e.g. not protruding so far that it hits other parts in an assembly).

Placement & Spacing

- Even distribution: Ribs should be placed thoughtfully across a panel to achieve uniform reinforcement. If you put all the ribs in one area and leave a large flat elsewhere, that flat area may still flex (and could even warp from uneven forming stresses). Distribute ribs across broad surfaces to break up large expanses of flat sheet.

- Avoid crowding: There is also such a thing as too many ribs too close together. If ribs are spaced too tightly, the sheet between them can warp or not form correctly, and you may not gain additional stiffness due to interaction. A good practice is to allow a spacing roughly on the order of 8–10× the sheet thickness (or more) between parallel ribs, so that each rib can form without distortion and the material between ribs remains flat.

- Align with load paths: Consider the directions in which the part will experience stress or bending. Ribs are most effective when oriented perpendicular to the primary bending direction. For instance, if a panel tends to bend left-to-right, adding a couple of longitudinal ribs (running front-to-back) will counter that bending. On the other hand, if a panel needs to bear a point load at a certain spot, you might radiate ribs out from that point or encircle it (like ribs around a mounting hole) to spread the load.

Orientation and Alignment

- Run ribs perpendicular to bending: As noted, ribs work by increasing stiffness in the direction of their cross-section. A rib acts like a beam – it’s much harder to bend the sheet across the rib (perpendicular to its length) than along the rib. So orient ribs to interrupt the expected bending lines of the part. A common technique is adding ribs across large flat spans in the weakest direction.

- Watch out for interfaces: Avoid placing ribs in areas that will interfere with other design requirements. For example, if a gasket needs to seal against the sheet, you don’t want a big rib creating a gap in the seal. Likewise, ribs on surfaces that must mate flush with other parts could be an issue unless accommodated. Plan rib locations such that they do not collide with screw heads, welded joints, or other features unless that’s intentional. Sometimes only a portion of a part is ribbed, while other zones are left flat for fastening or sealing.

- Consistent forming direction: It’s usually best to design all ribs to protrude on the same side of the sheet (all embosses up or all down). This way, the part can be formed in one orientation without flipping. If ribs need to go different directions, it may require multiple operations or more complex tooling.

Manufacturing Constraints

- Material stretch limits: Different metals have different ductility. Softer alloys (for example, mild steel or aluminum) can handle deeper draws and larger embosses than brittle materials. When designing a rib, consider the material – aluminum can often take a taller rib than the same thickness of high-strength steel before cracking. If you’re near the formability limit, you might need to reduce rib height or increase corner radii.

- Tool access and form method: The rib geometry must be achievable with the chosen fabrication method. Extremely long, straight ribs might be easy with a roll-former or roller bead tool, but a complex curved rib might require CNC programming with a rollerball tool, or stamping in segments. Likewise, very short ribs or isolated boss-like stiffeners might need a different tool (like a stepped punch). Ensure your design matches what the manufacturer’s equipment can do. Consulting with the fabricator early can help adjust dimensions so the ribs form cleanly.

- Alloy and temper considerations: If using a hardened material (like spring steel sheet), adding ribs may be difficult or require specialty processes. You may opt for a softer alloy that is then heat-treated after forming. Most common sheet metals (low carbon steel, 5052/6061 aluminum, stainless steel in annealed tempers) are suitable for embossing ribs as long as the geometry is reasonable.

Material & Thickness Optimization

One major advantage of incorporating ribs is the ability to use thinner sheet stock while maintaining strength. Rather than starting with a thicker (and heavier) sheet for rigidity, you can start with a thinner sheet and strategically add ribs to stiffen it where needed. This can yield significant material savings and cost reduction. For example, fabricators often reduce a part’s gauge by one step and add a rib, ending up with equal performance at lower weight. The key is to optimize rib patterns so that the part meets all its load and deflection requirements in the thinnest material possible. By judicious use of ribs, it’s feasible to replace what might have been a 2.0 mm thick part with a 1.5 mm sheet that has ribs – achieving the same rigidity with 25% less material. This approach is a cornerstone of lightweight engineering in automotive, aerospace, and electronics enclosures. Of course, there is a point of diminishing returns (too thin a base metal can’t hold shape even with ribs), but within practical limits ribs allow engineers to trade material thickness for smart geometry. The result is weight reduction without sacrificing structural integrity.

(In summary, when designing ribs: use shapes and dimensions that the material can form without failure, place ribs where they’ll counteract bending, avoid interferences, and exploit ribs to get the most strength out of the least material.)

Real-World Applications of Progressive Ribs

Strengthening ribs are employed across many industries to improve component performance. Here are a few examples of where you’ll commonly see ribs in sheet metal parts:

- Automotive: Car bodies and vehicle structures make heavy use of ribs. Look at the inner door panels, floor pans, hoods, and trunk lids – you’ll see stamped channel-like ribs and grooves that add strength without weight. Truck beds often have raised ridges for the same reason, to prevent the sheet metal from flexing under heavy loads. In chassis and bracketry, embossed ribs are added to thin steel brackets (for mounting engines, suspensions, etc.) to stiffen them instead of using thicker steel. The automotive drive for lightweighting (to improve fuel efficiency) means nearly every sheet metal part in a car is optimized with ribs or flanges for strength.

- Appliances: Household appliances use surprisingly large sheet metal panels (which would drum like a gong without reinforcement!). Washing machine shells, dryer and dishwasher panels, refrigerator interiors – these often feature formed rib patterns or dimpled embosses to prevent vibration and noise. For instance, the sides of a laundry washer might have several vertical ribs pressed into the sheet to keep it from wobbling during the spin cycle. These ribs also help the panels resist dents and give them a visually appealing texture.

- Industrial Machinery: Equipment enclosures, HVAC ducts, and machinery guards commonly employ ribs for rigidity. Large air-conditioning ducts, for example, have beads rolled into their sides to keep the sheet metal from “oil canning” when air pressure fluctuates. Electrical cabinets and machine enclosures might use a grid of crossed ribs to support big flat surfaces. Not only do these reinforcements improve strength, but in the case of HVAC they also reduce noise by suppressing panel vibrations. Industrial designers will often add ribs to metal panels anywhere a little extra stiffness is needed to prevent buckling or to meet deflection specs under load.

- Electronics: In electronics enclosures (like server chassis, computer cases, telecom equipment racks), weight and space are at a premium. Thin-gauge sheet metal is used to save weight, but it needs stiffening to support boards, drives, and power supplies. Engineers integrate ribs into the sheet metal chassis to reinforce mounting points and large spans. For example, a server case might have embossed ribs near where the power supply mounts, to ensure the frame doesn’t flex. Ribs in these applications can also aid in heat dissipation by increasing surface area (acting like a crude heat sink) – a double benefit for cooling. And as with other examples, using ribs here avoids having to jump up to a thicker metal sheet, which would make the product heavier and more costly.

Advantages of Using Progressive Ribs

In summary, incorporating progressive ribs into sheet metal designs yields a number of compelling advantages:

- Improved Rigidity & Strength: Parts with ribs are much more resistant to bending and flexing. The stiffening ribs act like reinforcements that greatly increase the static and dynamic stiffness of the part. This means better performance under load – panels stay flatter and brackets hold their shape under stress. In many cases, adding a rib can boost a part’s strength by an order of magnitude compared to an un-ribbed flat panel. Designers can achieve strength targets without resorting to thicker or heavier materials.

- Weight Reduction: Ribs enable lightweight design. Since you don’t need as thick of a sheet to get the required strength, you can drop down to a lighter gauge material. The ribbing pattern compensates for the lost thickness. This results in significant weight savings, which is critical in transport applications (lighter cars, planes) and even consumer products where shipping weight and handling are factors. Importantly, the weight savings come without major trade-offs – you’re not adding different material, just shaping what’s already there more intelligently.

- Optimized Material Usage (Cost Savings): Using thinner sheet stock not only cuts weight, it also cuts cost. Material is often a big portion of cost in sheet metal parts. By using the minimum material necessary (augmented with ribs to meet strength needs), you reduce waste and cost per part. Ribs deliver strength efficiently, focusing material where it’s needed instead of uniformly increasing thickness everywhere. This targeted approach can make a part cheaper and also sometimes simplifies fabrication (for example, a lighter part might be easier to handle or require less robust fixtures). Overall, you get more “bang for your buck” from the same piece of metal.

- Enhanced Performance (Vibration & Precision): As noted earlier, ribbed panels tend to vibrate less and produce less noise. This can improve the user experience (quieter appliances, less rattling in vehicles) and reduce fatigue stress from repeated vibration. Additionally, the added stiffness can improve dimensional stability – a rigid chassis will hold tolerances better and keep aligned components in place. Ribs can also be designed to serve functional roles like locating or aligning parts (e.g. acting as small stops or guides), further improving the product’s performance. In short, the part isn’t just stronger, it often behaves better – less noise, less flex, and even potential thermal benefits in some cases (due to increased surface area for cooling).

In the end, progressive ribs offer a smart engineering trade-off: by accepting a bit more complexity in forming, you gain a large increase in stiffness and structural performance. It’s a proven way to make sheet metal parts that are stronger, lighter, and more material-efficient – a winning combination in most design scenarios.

Reinforce Your Designs with Atlas Manufacturing

At Atlas Manufacturing, we specialize in leveraging progressive ribs and other advanced fabrication techniques to enhance sheet metal designs. Our team of experienced engineers can help you optimize the strength, weight, and cost of your sheet metal components by intelligently integrating ribs and other features. With our state-of-the-art Trumpf CNC punching machines (including roller tooling for continuous rib forming) and precision stamping capabilities, we form high-quality stiffening ribs efficiently and accurately – whether for prototypes or high-volume production runs. The result? Components that are lighter, stronger, and perfectly tuned for their application, all without unnecessary material or cost.

Contact us today to discuss how Atlas can support your next project with precision-engineered stiffening ribs. We’ll work with you from concept to production, ensuring your sheet metal parts meet the highest standards of quality and functionality. Let us help you reinforce your products and turn your design ideas into reality – all while leveraging the latest in sheet metal fabrication technology. Your next project deserves the strength of Atlas on its side!